HLA-based therapeutics: an entire drug pipeline is based on a patient’s race.

Our new paper

In JAMA Network Open 26 October 2023, (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2811111) we show for the first time in the history of drug development that an entire drug pipeline is unequally accessible according to patient's race or ethnicity.

When it comes to trial eligibility for HLA-based drugs, White patients are favored over Black individuals and other ethnicities. How could this happen? What would be the solutions to overcome such inequity? A primer is needed.

Understanding HLA.

In mammals, there's a set of genes coding for proteins that allow the immune system to distinguish between the “self” and external threats, i.e., the “non-self”. It is called the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC). This allows our bodies to recognize and eliminate harmful bacteria and viruses. It's also involved in anti-tumoral immunity, which aim at recognizing and eliminating cells that replicate abnormally.

In humans, the MHC is called the HLA complex, standing for Human Leukocyte Antigen complex. It consists of several genes that are highly polymorphic, meaning there are several different alleles for each gene across the world.

This ensures that each individual has a unique HLA identity, except for identical twins. HLA genes are located on the short arm of chromosome 6, and every individual has two alleles for every HLA gene.

Historically, serologic assays discriminated a limited number of epitopes defining serotypes (eg, HLA-A2), compared with molecular biology, which targets up to a single nucleotide difference, thus enabling deeper levels of definition (eg, HLA-A*02:01). In medicine, the HLA system is crucial for transplantations to reduce the risk of rejection by ensuring a good "match" between donor and recipient based on their HLA genes.

HLA-based therapeutics – the example of tebentafusp in uveal melanoma.

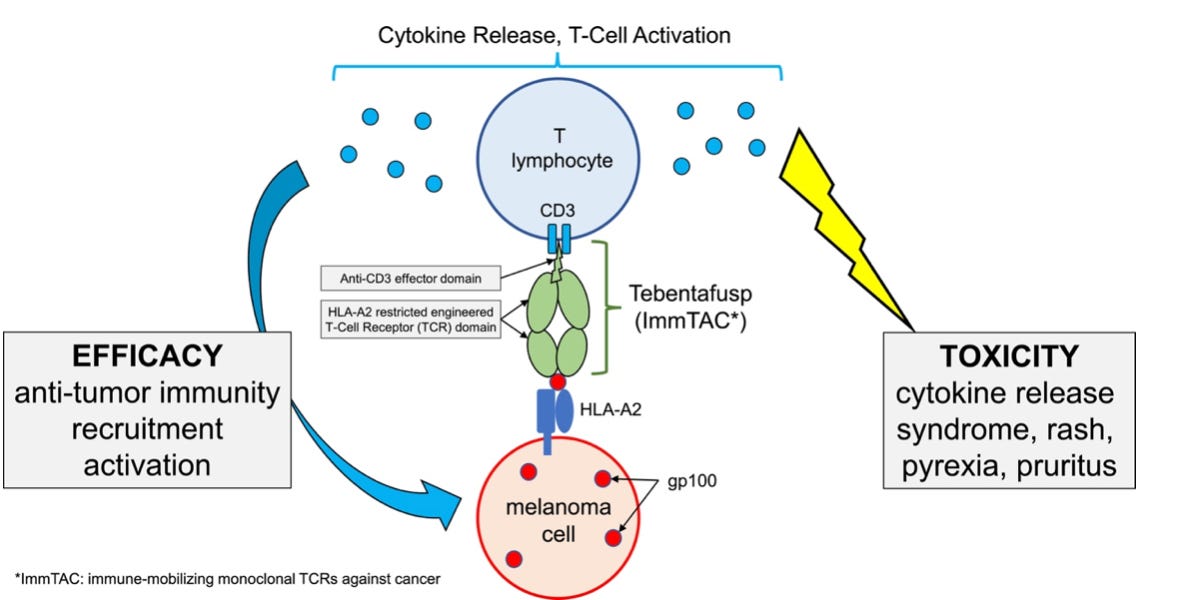

Another medical use of HLA proteins was the development of therapeutics designed to bind to specific HLA molecules. The most famous example is tebentafusp, which is a fusion protein, which targets the gp100 protein via its presentation by an HLA molecule. Tebentafusp can only be prescribed to patients which are HLA-A*02:01 positive, for the treatment of uveal melanoma, a rare and aggressive type of melanoma. As illustrated below, to target gp100, tebentafusp must bind to the gp100-HLA-A*02:01 complex.

In other words, a patient with advanced or metastatic uveal melanoma should first undergo an HLA-A genotyping. If the results reveal HLA-A*02:01 positivity, the patient will be eligible to receive the drug. Conversely, if the HLA-A genotype is, for instance, HLA-A23 and HLA-A24 (remember, every individuals has 2 alleles for one HLA gene): tebentafusp would be ineffective and should not be prescribed.

When tebentafusp was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2022 (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-tebentafusp-tebn-unresectable-or-metastatic-uveal-melanoma ), we noticed certain limitations in the clinical trial leading to its approval, detailed in this article (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1936523322000705 ).

We also noticed that the likelihood of being positive for HLA-A*02:01 varied by ethnicity. In the US, HLA-A2 was positive in 35% of African-Americans and 50% of Caucasian. In those, the HLA-A*02:01 subtype represented 96% of HLA-A2 serotype in Caucasian and, for instance, 53% in individuals of Asian/Pacific Islander. (ref https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019888599900155X)

In other words, according to one’s race, the likelihood of receiving the new drug -- tebentafusp -- differed. This observation triggered the project that I will now describe.

HLA-restriction into the entire drug pipeline – and systemic racial inequality.

In this new research, we examined all trials involving a therapeutic intervention that required participants to be positive for a specific HLA subtype(s). We identified 263 trials. Most of these trials focused on anti-cancer drugs (98%), and most were therapeutic vaccines (68%) or cellular therapies (28%). Importantly, the HLA subtypes being used to recruit patient were the HLA-A2 or HLA-A*02:01 subtypes in 87% of trials.

Next, using a global database of over 8 millions individuals worldwide (the CIWD 3.0.0 : https://www.ihiw18.org/component-immunogenetics/download-common-and-well-documented-alleles-3-0/ ), we estimated HLA subtypes prevalence across racial and ethnic groups. Based on the number of available slots in each clinical trial, and the required HLA subtype, we then estimated the likelihood of being eligible for such trials according to patients’ ethnicity.

We estimated that African or African American individuals had the lowest likelihood of being enrolled in such trials (33%), when individuals of European or European Descent were 1.6 times more likely to be eligible (53%). Data for other ethnic groups are shown in Table 3.

Causes and potential solutions.

We recognize that, by definition, because HLA subtypes are unequally prevalent across individuals, any HLA-based therapeutics will inherently be unequally accessible according to one’s race.

However, because of the HLA subtypes being currently used, mostly HLA-A2 and HLA-A*02:01, the pipeline is indisputably favoring European or European descent individuals over other ethnicities.

Does this mean this systemic bias was intentional? Our work never intended to suggest so. Historical reasons may have explained the predominant use of HLA-A2 in this pipeline. One trial included in our analysis was using T cells initially collected from a patient with the HLA-A:02:01 subtype. However, it is also possible that efforts to select more inclusive HLA subtypes were not incentivized.

A striking example is prostate cancer. African American individuals present higher incidence than White individuals. Our work identified 11 prostate cancer trials, 10 of which (91%) targeted populations with HLA-A2 serotype or HLA-A*02:01 allele, which are less prevalent in individuals of African descent than in those of European decent. In this case, the pipeline is offering less opportunity to the more affected patients.

In some cases, researchers may be aware of racial disparities posed by HLA-restriction. In the process of peptide identification, they may use HLA subtypes that are common in African American, Asian, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander populations. In one work, Stanojevic et al. concluded that defining specific peptides “beyond HLA-A*02-restricted epitopes could be useful when developing T-cell therapeutics for worldwide application”. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33832817/)

Conclusion

We described a drug development pipeline that is currently offering unequal access to therapies according to patient’s race. To my knowledge, such finding is unique. Overcoming HLA restrictions may be biologically challenging; however, solutions must be implemented whenever possible. The research community should aim to provide an equal access to innovative strategies regardless of race or ethnicity.