The starting dose is fair, but that is about it

Dose modification rules plague cancer trials

What if the experimental arm in a comparative trial had rules that allowed for higher dose-intensity than the control arm? If the trial found a benefit, you would ask is whether the benefit was driven by the dose modification rules or the novel drug. That’s the subject of our recent paper.

The REFLECT trial is a perfect example. This non-inferiority phase 3 trial enrolled patient with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in the first line setting. The trial aimed to demonstrate non-inferiority of lenvatinib (experimental) compared to sorafenib (control).

Rules applied to patients receiving 12 mg of lenvatinib had 3 steps of dose reduction: 67%, 33%, and 17% of the starting dose. In contrast, patients in the control arm could only lower the dose 2 times before stopping the drug, and the dose reduction were more pronounced: 50% and 25% of the starting dose.

These rules allowed for more dose-intensity (more drug is given) in the experimental arm. As a proof of concept: in the trial, similar rates of patients had a dose reduction in both arms (37% and 38%). However, likely due to the imbalance in dose reduction rules, the cumulative dose was higher in the lenvatinib group (88%) versus sorafenib (83%). Other trials had been described with such imbalance.

We conducted an analysis of the ASCENT trial, which studied patients with triple negative breast cancer. Our findings highlighted that the utilization of G-CSF, intended to prevent or reduce hemato-toxicity, may have allowed for higher dose-intensity in the experimental arm again due to unfair rules.

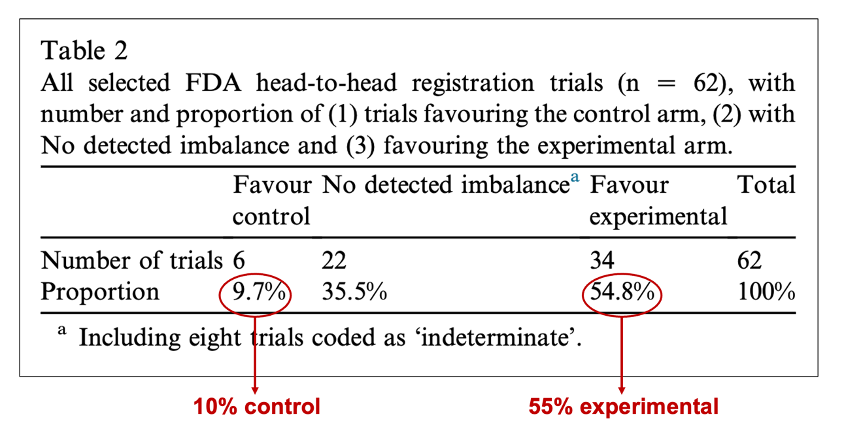

Both the imbalance in drug modification and the unfair G-CSF rules prompted us to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the frequency of this phenomenon in registration trials. To achieve this, we selected all comparative trials for FDA registration between 2009 and 2021, where we could compare rules between arms, and reviewed the reports and protocols. Our results were simply astonishing ! We found that in 55% of the trials, the rules favored the experimental therapy, while in only 10% of the trials, the rules favored the old therapy.

The implication of such findings is large, we conclude:

“It is impossible to know in all these cases whether the new drug is truly better than the old one, or if better outcomes were achieved by higher dose intensity.” One should always check for drug modification rules and G-CSF utilization in trials to better appraise the reported results. Lastly, regulatory authorities should ensure such rules are balanced in comparative trials to avoid bias against the control arm.