Treatment After Progression in Oncology Studies is Vitally Important

Our new paper is out now in BMC Cancer

What is treatment after progression and why does it matter? I tackled this question in newly published research in BMC Cancer, with my colleagues Alyson Haslam and Vinay Prasad.

This is one of the most important pieces of research I have done, and by the end of this essay, I hope you agree.

Let me set the stage

Cancer therapy typically involves a series of treatments, frequently referred to as first-, second-, or subsequent "lines". Each subsequent line of therapy is generally implemented when the disease advances. As such, patients often take a series of drugs, and have a series of breaks in their cancer journey.

Now remember: the goal of cancer medicine is to maximize survival and maximize quality of life, and, all else being equal, using the fewest drugs possible for the least amount of time— to minimizing toxicity, cost and therapeutic burden.

As such, trials have to test when and how to best sequence these drugs. Previously my collaborators, Haslam and Prasad discussed this in a seminal publication where they defined and illustrated when crossover, a type of post-progression therapy, is desirable and when it isn't. Today’s work goes one step further.

Three unfortunate scenarios.

Consider 3 scenarios.

In patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer, abiraterone was standard of care before a trial called LATITUDE started enrolling patients. The LATITUDE trial tested abiraterone earlier, in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer.

However, in LATITUDE, only 24% of control arm patients treated with a subsequent therapy received abiraterone. This is a clear example of substandard post-protocol therapy. This may affect the overall survival results, because your comparator, the control arm, is not being offered the optimal therapy. The trial cannot answer the relevant q: is it better to give abiraterone early or reserve it as we were doing? Instead it tests a useless q: is some abiraterone better than nothing?

How could this occur, you might ask? This represents the most disheartening aspect of the whole issue. Trials aiming for market dominance in wealthier nations, from which they reap most of their profits, may be carried out globally, including in countries with low to middle income. Regrettably, many patients in these countries do not have the best access to superior treatments once the trial has run its course, leading to biased survival results.

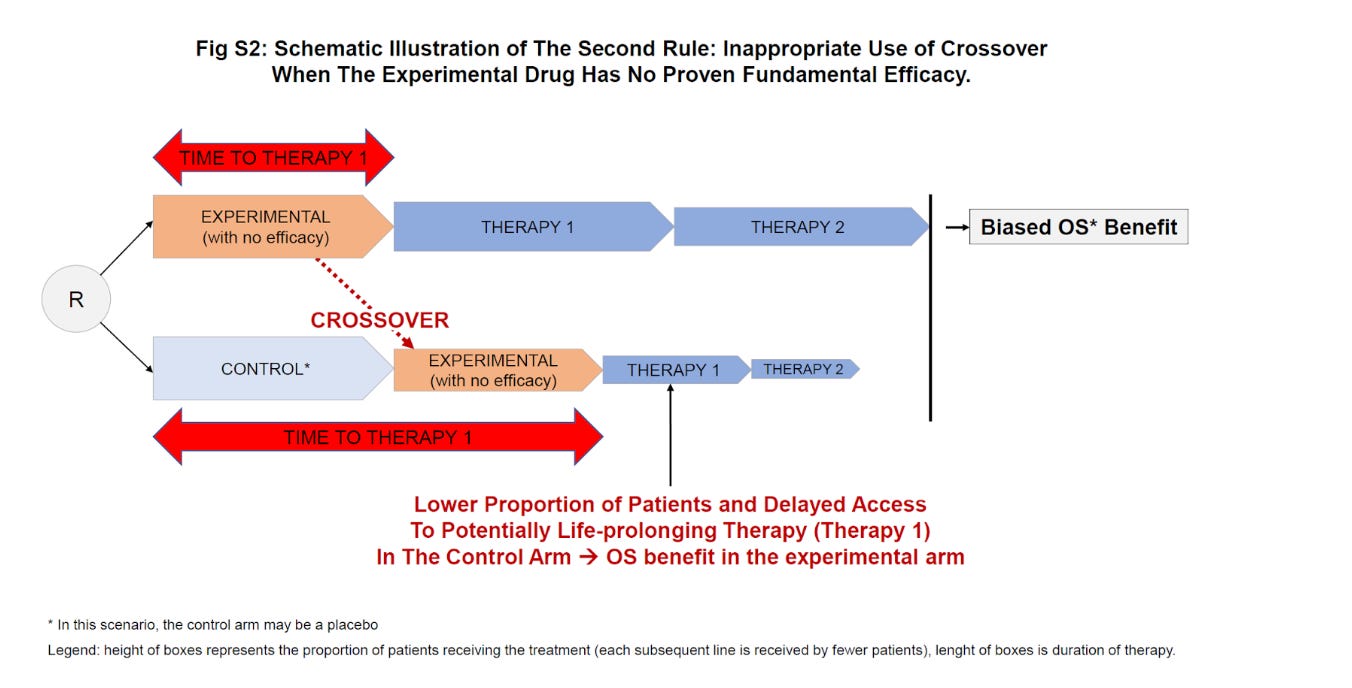

A second bad post-protocol usage of a drug is when a therapy without proven efficacy is provided upon progression in the control group. The IMPACT study trial tested sipuleucel-T – a type of cancer vaccine – in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Bizarrely, patients in the control arm received sipuleucel-T upon progression (they “crossed-over”). But let’s imagine the product had absolutely no efficacy, which is not implausible, this may have delayed access to life-prolonging therapies in the control arm patients. In the IMPACT trial, the observed survival benefit could not have been driven by the superiority of the new therapy in the experimental arm, but instead by delaying access to best therapy to the control arm patients. This kind of crossover should never happen. Below is an illustration from the supplementary appendix of our manuscript.

In a third undesirable scenario, the percentage of patients receiving any post-progression treatment within the trial is lower than in real-world conditions in both arms. This is entirely nonsensical given that patients participating in trials are typically healthier and more robust than the average cancer patient. Sadly, this probably occurs for the exact same reason as in the first scenario: trials enrolling in countries with suboptimal access to best care.

The effectiveness of ribociclib was evaluated in the MONALEESA-7 trial, primarily among patients receiving initial treatment for hormone-sensitive advanced or metastatic breast cancer. The trial compared ribociclib to a placebo, both used in combination with hormonal therapy. Subsequent treatments after disease progression were noted to be quite low, with 73% in the control group and 69% in the ribociclib group. However, real-world data indicates a higher utilization rate of up to 92% after initial hormonal therapy.

This raises the question: would we have observed the same survival benefits if both groups had maximized the use of all available follow-up treatments? Ultimately, there's no compelling argument to administer the drug earlier, risking increased toxicity, if future treatments can yield identical outcomes. Below is another illustration.

Now, onto our key findings.

With the 3 scenarios in mind, the significance of optimal care upon progression becomes more evident. A clinical trial that ensures appropriate post-progression therapy is likely to yield more reliable results than a trial that lacks sufficient or undisclosed data regarding post-progression treatment.

We conducted a comprehensive assessment over three years (2018 to 2020), reviewing trials published in top six journals (amounting to 275 trials), as well as those that led to FDA approval (totaling 77 trials). The results we present below are concerning. Our main findings indicate that only a small percentage of the publications (16.4%, or 45 out of 275) and FDA registration trials (11.7%, or 9 out of 77) had available post-progression data assessed as appropriate.

Solutions and a Roadmap for Healthcare Professionals.

A possible remedy for this issue could be for regulatory authorities to exclusively grant marketing authorization based on trials ensuring optimal post-progression treatment in both the test and control groups.

We introduce the '10 percent rules' to assist clinicians in evaluating post-protocol treatment. These rules simply reflect the expected standard of care in countries where most approvals are sought. They could be utilized by regulatory bodies and health technology assessment agencies in future evaluations of trial results.

Check out the full paper if you want to dive deeper in this topic. Thank you to all the readers, and let us know what you think !

The best we can do at present is compare between arms to see if differences in post-protocol treatment may account for differences in OS.

While agreeing this is a problem in interpretability of oncology trials, I don't foresee a landscape in which sponsors agree to dictate (and fund) post-protocol therapy, in which ECs will wave such protocols through, or oncologists accept sponsors making their treatment determinations for them.

Equally, the suboptimal treatment in countries less well-off than the USA or Switzerland is real-world. A different regimen or order of regimens may work fine where you have essentially unlimited cash to pay for therapies of marginal OS benefit, but something different in places where this is not the case. Cancer patients, and their physicians, in those places, also deserve to know what is the best option within their real-world limitations.

This is interesting work but there are bigger problems with recent FDA approvals, delinquent control groups, single-arm trials, non-robust endpoints, essentially a big recent departure from the need to demonstrate OS benefit in at least one, and optimally 2, well-controlled trials.

Good stuff -May be this would explain why ribociclib is the only CDK4/6 with an OS benefit...