Can I confidently say to patients that a 3-year structured exercise program may save their lives? The CHALLENGE trial (part 2)

Why I would not (yet) implement the CHALLENGE strategy

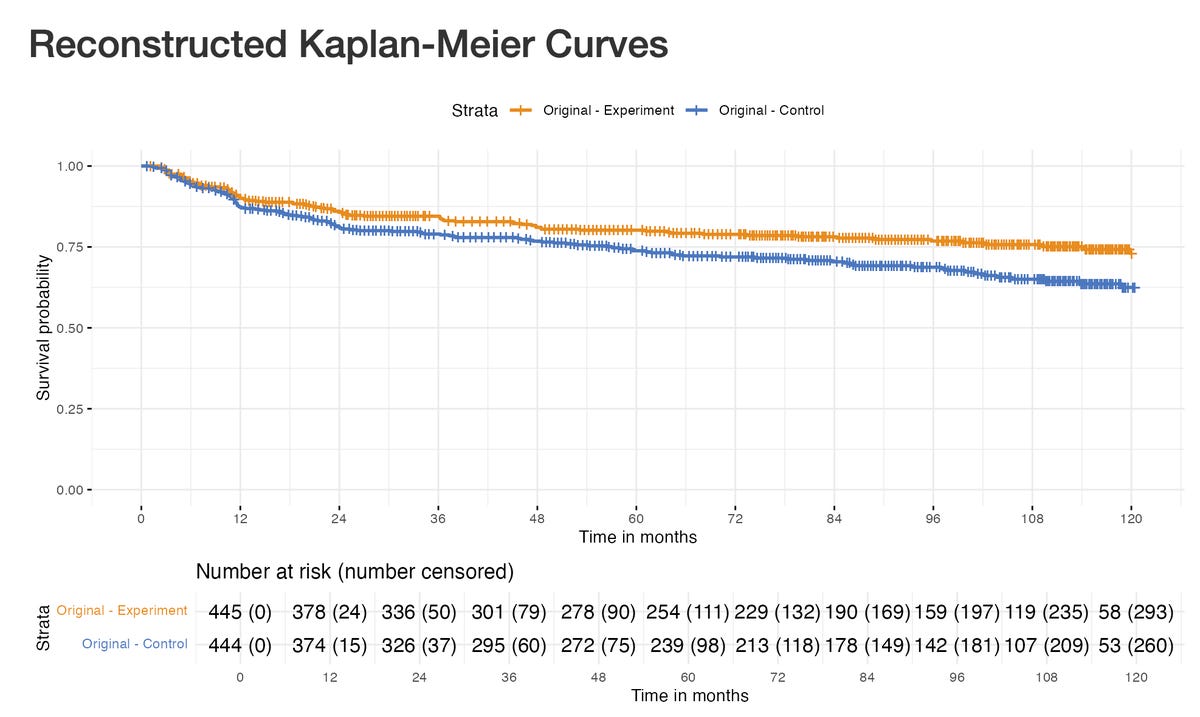

A brief recap: the CHALLENGE trial enrolled patients treated for colon cancer and adjuvant chemotherapy and randomized them to receive either health-educational materials only (control patients), or similar materials plus a 3-year supervised-exercise program (experimental patients). The trial showed a Disease-Free Survival (DFS) benefit, and an Overall Survival (OS) gain in patients randomized to receive the 3-year exercise program.

The trial was presented during the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology 2025 ASCO meeting by Pr Christopher Booth, MD FRCPC, on 1st June, and published the same day in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results triggered enthusiasm and headlines in media outlets.

In a first X Article, entitled "Can we challenge the CHALLENGE results?", also covered in the drugdevletter, I had a more cautionary take, mainly due to concerns about the possibility of informative censoring, with a focus on overall survival.

My first analysis led to two types of reactions

Many were happy to see a critical appraisal of the CHALLENGE study, which is a well-conducted, academic trial, and not studying a new, costly drug. We should appraise any trial without preconceived biases.

Others were unhappy, mainly, in my interpretation, because they were happy with the results (DFS and OS gain), and were happy with the intervention being studied (exercise), and therefore unhappy to see such a study – and results – criticised.

After all, why would one criticize that doing more exercise is beneficial?

Appraisal shouldn't be driven by personal preferences

I don’t see any justification for applying different standards to evaluate evidence regarding the intervention being studied. Some even advocated for changing practice the day after the presentation. Others downplayed the relevance of any critic of CHALLENGE, simply (I believe) because they love the supervised exercise programme and seem convinced it can only be beneficial.

I have 3 points to make here :

Why run the study if we knew for sure exercise was better in the first place ?

A 3-year supervised exercise program can be burdensome for patients (more on that later).

Imagine the guilt one may impose on a patient that is unable to undergo the adjuvant programme, for whatever reason. This is exactly the same with other adjuvant therapies in general. Poor communication can lead patients to believe that their cancer will return—or has already returned—because they couldn’t follow the adjuvant program.

Before discussing and proposing any additional treatment, or intervention, based on a survival gain, we must be confident that such gain is real. The same principles should apply whether it involves eating nuts daily, receiving chemotherapy, or committing to a three-year exercise program. As physicians, we cannot decide what is convenient or acceptable for patients; they should decide for themselves.

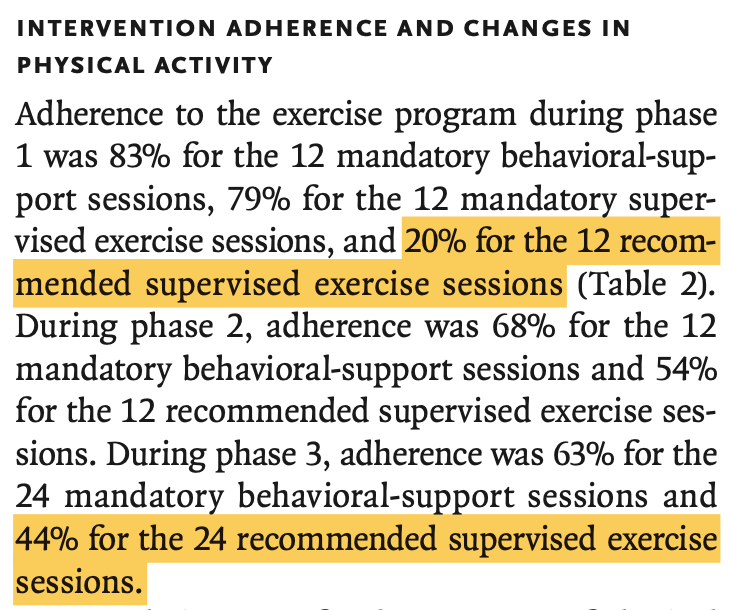

A burdensome program, at least for some patients

A 3-year supervised exercise program can be burdensome for many reasons.

This can come with time-toxicity: the time you spend doing exercise is not spent with your family, friends, etc. (more on time-toxicity in our work led by Vinay Prasad, here). You may have to travel to be able to attend the programme, etc.

Second, the supervised program can come along with financial toxicity: who will pay for your transportation, parking, etc.?

Additionaly, the program may be associated with side effects, and this is one finding of the CHALLENGE trial: "Musculo-skeletal adverse events occurred more often in the exercise group than in the health-education group (in 18.5% vs. 11.5% of patients)."

Burdensome, really?

From the CHALLENGE trial report, we can see that adherence to the program is far from easy. For instance, only 20% of patients attended the 12 recommended supervised exercise sessions of Part 1.

It’s likely that informative censoring occurred, let’s look at DFS now.

My core hypothesis is that patients randomized to the 3-year supervised program who left and were censored in excess within the trial, both for DFS and OS endpoints, may have been different from those remaining in the trial.

If these patients were frailer and more at risk of presenting the event, this could retain patients with better outcomes in the 3-year exercise group, potentially creating an artificial benefit.

Let’s consider a group race, which is relevant here. If we remove the running-time of patients who didn’t complete the course, the average time will logically – and artificially – increase.

While a 3-year exercise programme isn’t inherently toxic, it does come with a potentially significant burden, including time, toxicity, physical, and other challenges. This may select for healthier patients who are able to commit to the program.

Two BREAKING-ICE App© DFS sensitivity analyses.

When reporting time-to-event endpoints, it’s good practice to report both the time when each patient was censored (either with tick marks or circles) and the number of censored patients in brackets after the number at risk at each time interval. This type of reporting has been almost systematic in journals of The Lancet group for years.

The New England Journal of Medicine sometimes reports it, sometimes not.

It’s disappointing that the CHALLENGE trial report didn’t include the number of censored patients, nor tick marks or circles of censoring events: as shown below, the curves are perfectly smooth. Additionaly, there is no discussion about censoring as a potential limitation in the results’ validity.

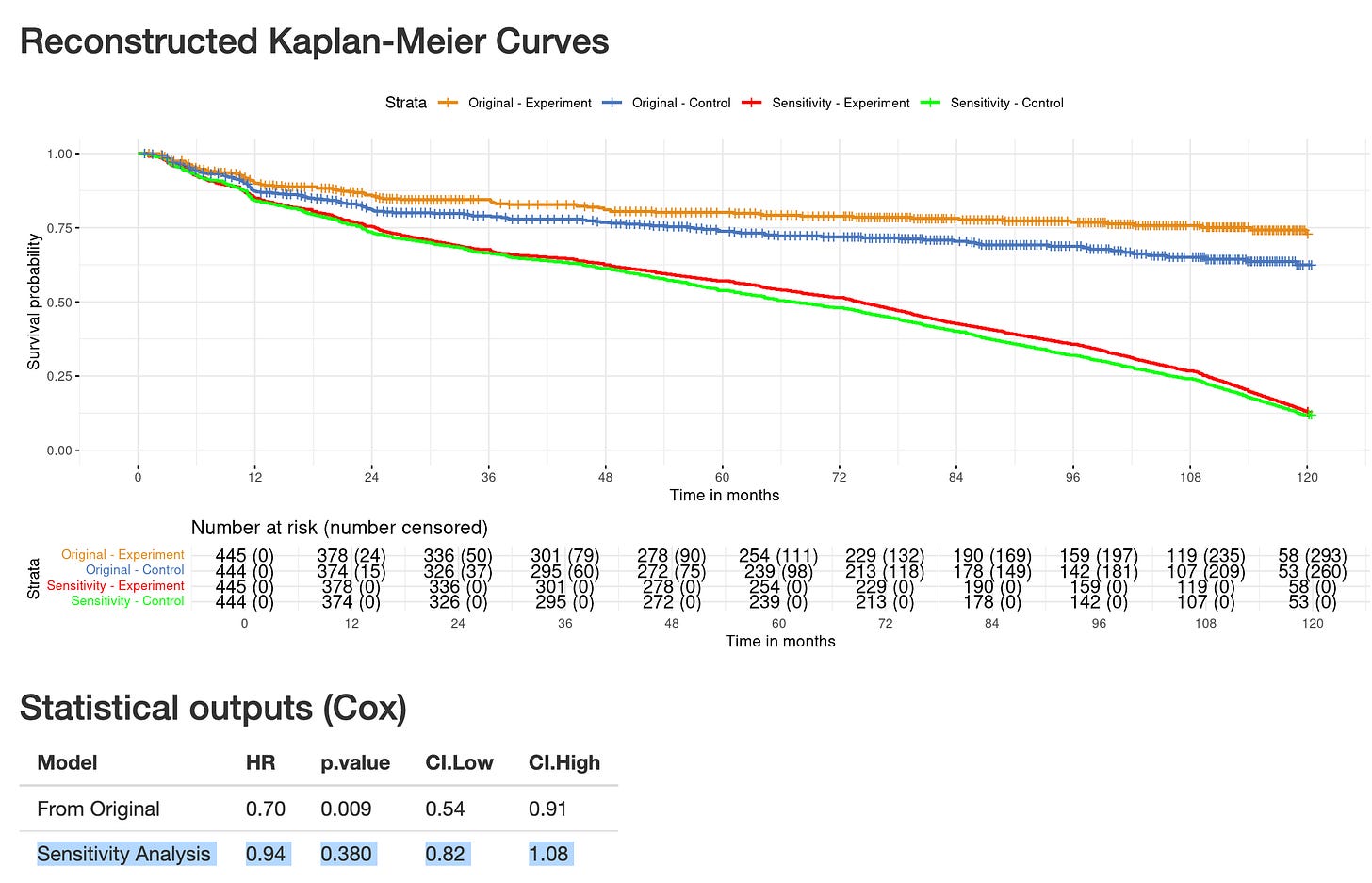

Fortunately enough, we have tools to estimate the numbers and distribution over time of censoring events, after digitizing curves, like the BREAKING-ICE App© (see previous post). I already conducted sensitivity analyses based on the OS results (detailed here). Here is the DFS, go on: https://www.timotheeolivier-research.com/breaking-ice, and select "CHALLENGE-DFS".

Firstly, you can see an excess of censored patients at early time points in the exercise group. Cumulatively, at 36 months, 19 additional patients have been censored in the exercise group as compared to the control group. If one hypothesises that only a fraction of those patients censored in excess would have presented a DFS event instead of being censored (n = 12), the results are becoming non-significant. (select "CHALLENGE-DFS-Sens1").

This is hardly an extreme assumption: it only changes the status of 15 % of censored patients in the arm with excess censoring during the first 36 months.

You can see that if you apply similar assumptions over a longer period of time, both curves now appear very close (select "CHALLENGE-DFS-Sens2"): it becomes difficult to fit a laser pointer between the red and orange curves!

Below is one screenshot, but the best is to visit the BREAKING-ICE App© and play with it: https://www.timotheeolivier-research.com/breaking-ice

The Reverse Kaplan-Meier Plots : another way to explore informative censoring.

The Reverse Kaplan-Meier plots basically invert all events into censoring ones, and vice-versa, and run the analyses again. Even though it is usually used to estimate the median follow-up duration in trials, it is a useful tool to explore whether censoring occurs. Tomer Meirson et al. elegantly used this method in their work published in the European Journal of Cancer (here).

In CHALLENGE, both the DFS and OS reverse Kaplan–Meier plots and the Cox model outputs suggest that informative censoring may have occurred (see: https://www.timotheeolivier-research.com/reverse-km, select "CHALLENGE-DFS", and "CHALLENGE-OS" and look at the statistical outputs).

These results reinforce the concerns that informative censoring could have occurred in CHALLENGE.

A surprising deviation from the “Common Sense Oncology” principles

“Common Sense Oncology” – or CSO – is a movement born in 2023, with a mission I fully share: “To ensure that cancer care focusses on outcomes that matter to patients”. Many friends and researchers I admire belong to this movement for which I have respect. Amoung the CSO founding members, Pr Christopher Booth is considered the “father” of CSO. He is also the last and corresponding author of the CHALLENGE trial report.

Earlier this year, CSO published guiding principles in The Lancet Oncology for the “design, analysis, and reporting of phase 3 randomized clinical trials”. Although aimed primarily at systemic anticancer therapy trials, the principles can – as the authors note – "be adapted for trials evaluating other interventions”. One principle I strongly endorse is:

“(7) censoring should be detailed, and sensitivity analyses done to determine its possible effects”

Yet the CHALLENGE publication falls short on this key point – one that is especially relevant to the trial.

Since my initial posts, I wrote a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine precisely asking for clarification, but it was rejected: “Many worthwhile communications must be declined for lack of space.” Let’s see which letters will be chosen: my only hope is that the potential for informative censoring will be addressed in the correspondence. I also see this as an opportunity for the CSO movement to offer clarification (see “Takeaway points” below).

Let’s run the “Common Sense Oncology” sensitivity analysis

Amoung other guiding principles, CSO proposes that:

“One of the sensitivity analyses should assume that patients progress at time of censoring (if progression-free survival or disease-free survival are endpoints), thereby providing curves for time to treatment failure, in which treatment failure represents dropping out of the trial as well as disease progression or recurrence”

Even though such analysis is not exactly reflecting time-to-treatment failure (TTF), as there can be censoring in TTF endpoint (for instance at data analysis for patients still under therapy), I have performed the analysis, now look at the HR = 0.94 (0.82- 1.08), and the green and red curves are essentially superimposable.

In short, this additional sensitivity analysis – conducted in line with the CSO principles – adds another layer reinforcing concerns for informative censoring.

Takeaway points

There is a difference between, on the one hand, believing that sedentarism is detrimental to one’s health and that physical exercise should be promoted – which was the control arm of CHALLENGE – and, on the other hand, asserting that a 3-year supervised exercise program will reduce your risk of recurrence and even your risk of death.

Patients with cancer, particularly after adjuvant therapy, have already experienced enduring suffering and may feel exhausted: a 3-year intensive exercise program is not trivial. We should not downplay it, in the same manner we do not trivialise 3-years of osimertinib in the ADAURA trial. Every intervention can have downsides, including those appearing to be automatically beneficial.

My concern is that informative censoring could have driven, at least partly, the reported results of the CHALLENGE trial, both for DFS and OS. This is not intended to be a criticism of the investigators. Informative censoring can occur in well-conducted and well-designed studies, and should be handled through sensitivity analyses or acknowledged as a potential limitation. I have already congratulated the authors, investigators, and patients for this impressive trial.

Finally, as noted earlier, even though the initial report falls short on addressing informative censoring, I believe the CHALLENGE trial offers an important opportunity for the CSO movement to demonstrate – unambiguously – that it applies the principles it advocates, transparently, whether or not its members are involved in the study. In my view, such transparency would be essential for a movement that aims to grow.

With such uncertainty, and until these concerns are resolved, I feel uncomfortable asserting to patients that a 3-year structured exercise program may save their lives.

Thank you so much. I don’t wanna make people feel guilty or lesser because they can’t do what people who are privileged with better health, more money, etc. can. The old laser pointer between the lines on the curve line was great to hear. You’re doing a great job of bringing us very useful and thoughtful information. Great job.